| Actors: Susanne Lothar, Ulrich Tukur Director: Michael Haneke Genres: Indie & Art House Sub-Genres: Indie & Art House Studio: Sony Pictures Classics Format: DVD - Black and White - Subtitled DVD Release Date: 06/29/2010 Original Release Date: 01/01/2009 Theatrical Release Date: 00/00/2009 Release Year: 2010 Run Time: 2hr 24min Screens: Black and White Number of Discs: 1 SwapaDVD Credits: 1 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 7 MPAA Rating: Unrated |

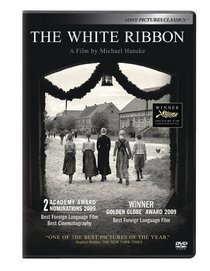

Search - The White Ribbon on DVD

| The White Ribbon Actors: Susanne Lothar, Ulrich Tukur Director: Michael Haneke Genres: Indie & Art House UR 2010 2hr 24min A village in Protestant northern Germany. 1913-1914. On the eve of World War I. The story of the children and teenagers of a choir run by the village. |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

Similarly Requested DVDs

|

Member Movie ReviewsReviewed on 1/16/2011... A movie with no definite conclusion. Well done in black and white with subtitles, (I love foreign films) this movie gives no answers to the strange happenings throughout the film. There is narration, which I do not mind, and no explanation as to who perpetrated the evil acts in the film. I watched it all the way through and was left hanging at the end. Fortunately I watched my library copy so I did not waste any money on this garbage, only time. Maybe I should have read the book first, or maybe they will write a movie tie-in later so someone can explain what (was supposed to have) happened. This bandwagon should have crashed before it began. 1 of 1 member(s) found this review helpful. Reviewed on 8/6/2010... Specious attempt at explaining roots of 20th Century Fascism *** This review contains spoilers *** We're told at the beginning of 'The White Ribbon', that this is a story that seeks to "clarify things that happened in this country", as if to imply that we're about to gain some insight into the origins of Nazism. But director Michael Haneke has made it clear that he was aiming for a more generic understanding of the roots of Fascism when he was quoted as saying that the film is about "the origin of every type of terrorism, be it of political or religious nature." Note that Haneke doesn't speak of "Nazism" or "Fascism" but uses the modern term "terrorism" to describe the actions of many of the characters in his film. The setting of Haneke's tale is the fictional village of Eichwald, right before World War I. There is virtually no effort to link the story to actual historical events except for the specific reference to the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand and the start of World War I at the film's end. Haneke does this because his story is really a PARABLE; by making it (in part) applicable to all nationalities and to different historical epochs, Haneke, in effect, minimizes the responsibility of the German and Austrian peoples who lived during the time leading up to the Holocaust and participated in it, either directly or indirectly. If his parable is universally applied, the unique horror of Nazism can't really be any worse than any other atrocities committed by other groups in history. The generic nature of his story (or parable), bears this out. Despite his insistence to the contrary, it remains obvious that 'Ribbon' IS also Haneke's attempt to explain the rise of the Third Reich. He is not unlike a bevy of German and Austrian filmmakers who utilize a fictional melodramatic narrative to assuage their own guilt (as well as an attempt to speak for the collective guilt of a nation). It's not easy being German or Austrian when your recent ancestors are linked to mass murderers. If the ancestors are portrayed as likable, normal people but also capable of violence (or supporting violence), this would lead to unpleasant feelings of cognitive dissonance. But what if the history is reduced to a more simplistic formula consisting of monsters, victims and saints? The viewer no longer has to be confused rooting for a complex Tony Soprano type of character—an extremely violent man who is also likable and sympathetic. In 'The Reader', the monsters are the cold Concentration Camp guards in the docket, who won't admit their guilt. The victim, however, is Hanna Schmitz, the guard who is presented as a tragic figure, done in by ignorance. During the trial, it was her compulsive need for order that prevents her from allowing the prisoners to escape. The saint is the protagonist, Michael Berg, who can still have sympathy for the 'tragic' Hanna as well as offer to pay money to a Holocaust victim's foundation. Haneke also must create his share of monsters. In doing so, a guilty populace no longer has to believe that their grandparents were part of a 'normal' silent majority that supported Hitler. How could anyone's ancestors be like the Eichwald town doctor, pastor or baron? The doctor is someone who sexually humiliates his long-term mistress, the midwife, as well as sexually abuses his own daughter. The pastor utilizes corporal punishment to raise his children, which leads to acts of revenge on their part. What's more, he promotes unhealthy sexual feelings in his children, by denouncing masturbation as a sin. The Baron neglects workers on his estate, leading to the death of a worker's wife in a work-place accident. He also neglects his wife, the Countess, who ultimately leaves, after she accuses him of allowing a lot of unhealthy stuff to go on in the village. Like Hanna Schmitz whose behavior was excused on the basis of being raised in a bad environment, the White Ribbon kids also get a free pass. They are the 'victims' of the monstrous fathers and enabling mothers. How can any child be completely responsible for crimes committed as an adult if the upbringing was so horrendous? This is the film's 'hook'--it's the kids who committed most (or all) of the crimes in the village: the doctor is injured after his horse falls in an encounter with a trip wire; the baron's son is hung upside down in the forest and caned; and a mentally challenged kid is tortured. The kids cover their tracks by appearing en masse at the victim's home, asking if they can be of any help. Finally, there is the 'saint'--here is the character which a guilty audience can identify with ('Hey my grandfather didn't support Hitler at all—he was apolitical and a nice guy to boot!) The school teacher fits the bill perfectly. Not only does he save the hapless Eva after she's fired but figures out who's responsible for the crimes committed in the village and has the guts to reveal the ugly truth to the town's power broker, the Pastor! While it is very wrong to blame today's generation in Austria and Germany for the sins of the parents and grandparents, it is equally disturbing to realize that there is a pattern of denial amongst the younger generation in regards to the idea that the enablers of the Holocaust were not the monsters, victims and saints depicted by Mr. Haneke but rather ordinary people who one could easily identify with. Despite its facile explanation of the roots of Fascism, the White Ribbon has some value, precisely because it sparks debate. With its austere, Bergman-like, black and white cinematography, and recreation of a bygone era, Haneke scores points for atmosphere. But instead of focusing on 'why' the Holocaust occurred, the 'what' and 'how' would have been more than sufficient. 0 of 1 member(s) found this review helpful.

|